- Home

- Gallery and Artists

- About BAMM

- Members Area

- Resources

- Prompts from the Pros

- Prompts from the Pros - Sophie Robins

- Prompts from the Pros - Rachel Davies - Interwoven

- Prompts from the Pros - Lawrence Payne

- Prompts from the Pros - Alex McHallam

- Prompts from the Pros 2 - Escape with Bonnie Fitzgerald

- PftP2 Francesca Busca Eco Artivism - Fabric

- PftP2 Francesca Busca Eco Artivism - Metal

- Prompts from the Pros 2 - Francesca Busca Eco Artivism - Paper

- Prompts from the Pros 2 - Francesca Busca Eco Artivism Plastic

- Prompts from the Pros 2 - Joanna Kessel

- Prompts from the Pros - Helen Miles

- Prompts from the Pros - Julie Sperling

- Prompts from the Pros - Kelley Knickerbocker

- Prompts from the Pros - Marian Shapiro

- Prompts from the Pros - Rachel Sager

- Materials & Techniques

- History of mosaic

- BAMM Talks and Demos

- Useful links and groups

- Suppliers

- Prompts from the Pros

- Workshops/Exhibitions

- News

- Supplier’s

British Association for Modern Mosaic

Resources: Mosaics in history

A Five Thousand Year Heritage

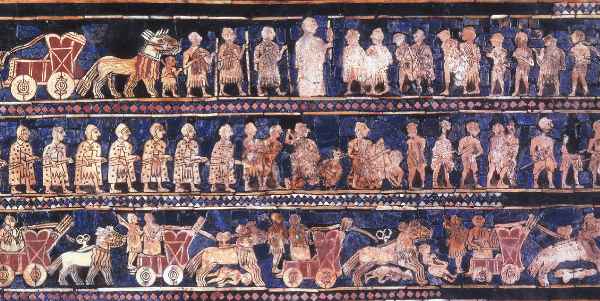

Perhaps some of the oldest mosaic art discovered can be traced back to the birth of civilisation in the fertile lands between the Euphrates and the Tigris. Excavations in ancient Sumeria and Mesopotamia have revealed already quite advanced mosaics. Great columns were found studded with geometric pattern formed from ceramic cones pressed into the mud walls. The most sophisticated of these ancient mosaics can be found in the British Museum in London. Known as the Standard of Ur, pictured above, this small box is decorated on four sides with intricate images of royal procession in shell, lapis and red limestone.

The early Greek pebble floors and the first great mosaic artist

The early Greek pebble floors and the first great mosaic artist

Archaeological evidence of pebbles being used to create patterns on floors can be found in Greece dating back to the 5th and 6th centuries BC. These early black and white pavements developed alongside the flourishing of Greek architecture, first incorporating floral motifs and borders then figures and stories. In ancient Olynthos a pavement depicting the hero Bellerophon riding on Pegasus dates back to around 415 BC.

Further north in Alexandra’s birthplace, the Macedonian City of Pella the development of mosaic art can be traced further. The large pebble floor mosaics here dating from around 300BC show highly sophisticated draughtsmanship and the introduction of portraying form through shading. One of the later hunting mosaics from Pella bears the name of it’s maker one Gnosis, this small Greek inscription perhaps marks a turning point for the mosaic craftsman, a level of skill and acknowledgement that deserved recognition.

The birth of tesserae

Soon after the Pella mosaics were completed the first mosaics began to appear which used cut stones in their fabrication. This development enabled the first flowering of the classical styles of mosaic making that were to sweep the world with the expansion of the Greek and Roman civilisations. Cut tesserae enabled the flowing courses of placed tesserae to enhance and describe the forms of the designed image. The move away from pebble to cut stone also brought to the mosaic maker a much wider range of colours as the various stones of the Mediterranean were brought together to form a new palette.

The Roman flowering

The Roman flowering

Along with many other art forms the emergent Roman empire adopted mosaic art for it's own. Mosaic art developed to a new level of design and craftsmanship and spread across the expanding Roman empire across the Mediterranean into Africa and Northern Europe. Mosaic craftsman travelled the known world and in each new Roman province local workshops were founded. Many of these regional mosaic workshops developed their own styles pushing the art form on to greater and greater heights.

The Romans took as their theme many aspects of everyday life as well as the great stories and legends of the gods and heroes. Today pictorial Roman mosaics form a vital part of the evidence of life in Roman times, showing often mundane, backstage details of everyday life: actors preparing to go on stage; animals being trapped for the circus; or the face of a Woman from Pompeii. Mosaics formed sophisticated patterned floor and complex stories, even puzzles.

The Romans took as their theme many aspects of everyday life as well as the great stories and legends of the gods and heroes. Today pictorial Roman mosaics form a vital part of the evidence of life in Roman times, showing often mundane, backstage details of everyday life: actors preparing to go on stage; animals being trapped for the circus; or the face of a Woman from Pompeii. Mosaics formed sophisticated patterned floor and complex stories, even puzzles.

Most of these mosaic were located on floors, though it was during the Roman era that wall mosaics start to develop further. This wall mosaic were restricted mostly to niches and smaller panels and it is here that glass mosaic starts to take hold.

In Britain alone evidence of over a thousand mosaic from the Roman period have been documented with significant clusters around the great Roman cities, though often in satellite rural locations, presumably as these have a greater chance of surviving to the present day. Fantastic Romano British floors can be seen in situ at Roman Villa excavations at: Lullingstone in Kent; Chedworth in Gloucestershire, Fishbourne in Sussex; Brading on the Isle of White. More still can be seen in museums across the country.

In Britain alone evidence of over a thousand mosaic from the Roman period have been documented with significant clusters around the great Roman cities, though often in satellite rural locations, presumably as these have a greater chance of surviving to the present day. Fantastic Romano British floors can be seen in situ at Roman Villa excavations at: Lullingstone in Kent; Chedworth in Gloucestershire, Fishbourne in Sussex; Brading on the Isle of White. More still can be seen in museums across the country.

The Christian Church takes the reins.

The Christian Church takes the reins.

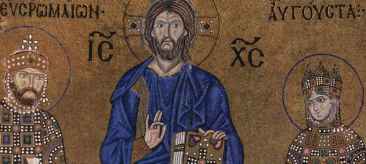

As the Christian religion spread through the communication routes of the Roman Empire Christian symbols began to appear in the mosaics, often along side the pagan images and almost indistinguishable. But soon the Empire itself was to turn Christian and in 427 the 'Codex Theodosianus' forbade the use of sacred symbols in the pavements of the Eastern Empire, holy images were not to be trodden under foot. And so mosaic art was lifted from the floor and became the adornment for the new churches. Glass manufacture developed along side this new direction to produce glass pastes and gold tesserae that would light up the now holy images.

For the mosaic artist this transformation was more than just a chance to work standing up. The client for mosaic had changed too, from the quite wealthy individual in their private premises to the vastly wealthy church hierarchy with ever greater buildings. Mosaic now had to cover huge areas, incorporating architectural feature. More importantly than this the themes now changed, no longer were images of the everyday needed. Now the designs were to bring inspiration and teaching and to demonstrate the idealised path.

And so some of the most spectacular mosaics were created, great golden ceilings filled with saints and patrons, ever more splendid ceilings demonstrating the power and wealth of the Christian Church in Europe.

And so some of the most spectacular mosaics were created, great golden ceilings filled with saints and patrons, ever more splendid ceilings demonstrating the power and wealth of the Christian Church in Europe.

This Byzantine tradition of mosaic making became very stylised as the church itself centralised. With the breaking away of the Eastern church this mosaic style continued unbroken to the present day.

Islam and mosaic art.

The early clashing and interweaving of Islam and Christianity saw much flow of artistic culture between the two religions. Differing waves of iconoclasm saw mosaic tradesmen travelling across the medieval world looking for work. In the 600-700's great mosaics were created under the direction of the Caliphs. The Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and the great Mosque in Damascus saw the beginnings of a new direction for mosaic within the Islamic tradition.

The early clashing and interweaving of Islam and Christianity saw much flow of artistic culture between the two religions. Differing waves of iconoclasm saw mosaic tradesmen travelling across the medieval world looking for work. In the 600-700's great mosaics were created under the direction of the Caliphs. The Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and the great Mosque in Damascus saw the beginnings of a new direction for mosaic within the Islamic tradition.

The late Medieval World

The fourteenth century saw the decline of mosaic art in western Europe. Despite the fact that some of the greatest artists of the early renaissance began by creating the cartoons (designs) for mosaics: Cimabue; Giotto; Ghirlandaio; Titian; Tintoretto; Veronese. The rise of the great fresco painters ended the dominance of mosaic. Mosaic art would go into a long decline as a mere imitator of painting, the mosaic artists pushing to ever more extreme lengths to look like painting with smaller and smaller tesserae and vanishing grout.

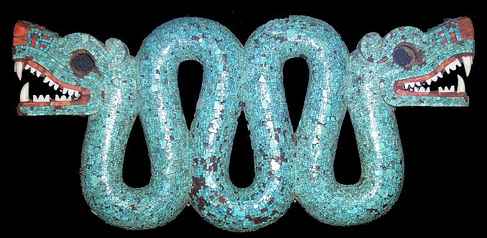

This decline was oblivious to the potential for mosaic art then being revealed by the opening up and plunder of the new world, it would be many hundreds of years before the impact of Amero-indian mosaics such as this would be felt in the mosaic world.